Human Flower Project

Friday, November 02, 2007

Yard Art: Toiling for Paradise

Jill Nokes, a generous contributing writer here, settles in deep with twenty yard artists from across Texas.

The Houston home of Cleveland Turner

better known as “The Flower Man”

Photo: Krista Whitson, from Yard Art and Handmade Places

“Who wants to see a hut?”

A reasonable question, asked by Sam Mirelez of San Antonio, Texas. It explains—in part anyway—why Mirelez models his aluminum birdhouses not on the homes in his neighborhood but the Eiffel Tower, the Alamo, and many another monument of world renown. It may also have something to do with why you baby a big old climbing rose or keep searching for another variety of muhly grass to add to your collection. Property brings out the show biz gene.

But for the thousands of us meekly coddling and neglecting our surroundings, there are a few like Mirelez. He is one of twenty remarkable Texans featured in Yard Art and Handmade Places, Jill Nokes’s exploration of extraordinary home environments across the state. Anyone who has battled the elements (like fatigue) to sustain something beautiful in the yard will not fail to be humbled by the ambitions and achievements of Nokes’s subjects. They’ve made palm tree jungles, streetside history lessons and cathedrals of junk, all of them more to be admired since, in many cases, the huts are just out of sight.

So far as we know, “Naives and Visionaries,” an exhibit mounted at Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center in 1974, was the first long look at yard art and related folk art installations (did that term exist then?). Subsequent books and shows on this phenomenon have tended to steer one of two ways. Many, like John Beardsley’s Gardens of Revelation, dwell on these efforts as idiosyncratic, as art—the creative outpourings of talented individuals. Other presentations, like Arte Entre Nosotros (Art Among Us), curated by folklorists Kay Turner and Pat Jasper in the 1980s, see yard art primarily as an expression of regional, ethnic and religious traditions.

Nokes partakes of both these approaches – in fact, folklorist Pat Jasper was an advisor and early collaborator on the project. But Nokes’s book takes a fascinating step beyond. A landscape designer herself, she possesses a stunning capacity to evoke the numinous effects of space. Every chapter begins with an extended scene-setting description; many of them are such sensoriums of language you alternate between philosophical reflection and beads of sweat.

Here Jill introduces “Stories from the Panhandle”:

“The expansive flatness, the vacant air, and the seamless connection of earth to sky all contribute to a sense of unfamiliar and uncomfortable exposure. The uninformed visitor convinces himself that there is no reason to feel so small and insignificant when surrounded by all this space, and in self-defense retreats into numbed boredom, deciding instead that there is really nothing interesting to see….In the winter, blizzards often roar in on 50-mile-an-hour winds to hammer the frosty ground, only to be replaced by scorching summer temperatures and drought. Most rain, when it comes, arrives in June and can range from twelve inches in the west to twenty-one inches in the northeast. Delivery of this scant rainfall brings to mind the old joke about the rancher who, when asked by the stranger how much rain he got that year, replied, ‘Oh, about fifteen inches, and I can remember the night we got it!’”

The windbreak on the Owens ranch, Deaf Smith County, Texas

Photo: Eldon and June Owens, from Yard Art and Handmade Places

Nokes proceeds to look at three places that no folklorist or art connoisseur would notice – huge windbreaks composed of a thousand or more trees, great Ls of green that some determined flatlanders have managed to grow on the otherwise brown expanse of north Texas. These living fortresses make it possible to sit comfortably on an outdoor patio while the wind drives 40 mph.

With many years of landscape work behind her, Nokes evinces as much excitement over the Clark family’s “expertise with heavy equipment, their skill at grading and their capacity for flat-out work” as she does for Rufino Loya’s delicious Casa de Azucar (House of Sugar) where ” concrete flowers dot the perimeter like hard candy candle holders on a grocery story birthday cake.”

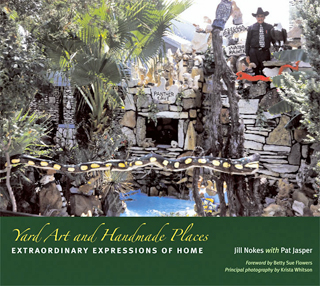

Yard Art and Handmade Places

Yard Art and Handmade Places

By Jill Nokes, with Pat Jasper

University of Texas Press, 2007

Throughout this handsome book, photographs by Krista Whitson – as well as pictures by Nokes and others – complement Jill’s prose and many intriguing excerpts from her interviews—a combination that transports us into these wondrous places. A good listener, she has drawn out the secrets of her subjects’ motivations.

“Being on duty twenty-four/seven put me more or less in a cubicle, and every day the walls of that cubicle got higher and higher,” Joe Smith, the lifelong town doctor of Caldwell, Texas, told her. “Art provided for me an escape route and allowed me fly over the top of that cubicle. I chose that route, and I enjoy it to this day.”

We at the Human Flower Project especially relish how acutely Nokes perceives the social sphere – as a kind of weather that can alternately prod, defy, limit, and flex the creative impulse. For Ruben and Irma Gutierrez, ornamentation of their yard stakes claim to right of pride where Indian ancestry has been muffled and Latino families lost their homesteads along the San Marcos River. Ira Poole’s pedagogical front yard in Austin – with its Statue of Liberty and sculpted maps—extends his career as a classroom teacher. Moving the opposite direction, Charlie Stagg retreated into his East Texas creation, a haven from his parents and a den to inhabit when the larger art world would not embrace the sculptures he had made to sell. Tim and Keith Ann Gearn have opened outward with a Ferris wheel—providing both a community landmark and a local spa on spokes. Sam Mirelez’s forest of birdhouses began with one anniversary gift.

Sam and Lupe Mirelez before their front yard in San Antonio

Photo: Krista Whitson, from Yard Art and Handmade Places

Most vividly, perhaps thanks to her many years of study and work in horticulture, Nokes senses how such environments—and their makers—change over time. Unlike paintings that hang in museums, these creations are subject to the pummeling and blazing of Texas itself. “I just found out that one of the windbreaks I featured in the book (June and Eldon Owens) was almost completely stripped in a freak hail storm on Wednesday,” Jill wrote October 12. “This was the same year they had noticed record numbers of pheasants roosting in their rare strip of woodlands.”

Such development and decline, what we savor in flowers, are human traits. We see Carol and Richard Blocker grow from nonchalant hobbyists, to obsessive and competitive cactus collectors, to kindly eminences of the succulent club scene in San Antonio – mentoring others and kicking back to enjoy their lot-sized “dish garden.” A moving finale is Jill’s portrait of Evelyn Blazek, now approaching her 90th year, Chinese tallow and privet creeping toward the sacred garden she has tended for more than three decades. What Nokes writes of Vidor’s Charlie Stagg holds true for all these extraordinary makers—as for the ordinary, with one rose on a trellis. “The structures themselves are as fragile as the life that built them.”

Note: Jill Nokes will give a slide lecture and sign copies of Yard Art and Handmade Places at the Texas Book Festival in Austin, Sunday Nov. 4, in the “Lifestyle Tent” at 10th and Congress, “right in front of the gates to the Capitol” from 2:00-2:45.

Art & Media • Culture & Society • Gardening & Landscape • Permalink