Human Flower Project

When Did You Last Go Wild?

Roads and human egos have depleted the U.S. wilderness. The EarthScholars coax us back out of doors, to consider the plants, animals and perspective living there. Thank you, Jim and Renee.

Fireweed growing in Maroon Bells Wilderness Area, Colorado

Photo: snrephotos

By James H. Wandersee and Renee M. Clary

EarthScholars™ Research Group

The earth’s vegetation is part of a web of life in which there are intimate and essential relations between plants and the Earth, between plants and other plants, between plants and animals.—Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Wilderness areas provide plant enthusiasts – and anyone else with eyes to see and a mind to wonder— with occupations for a lifetime. In the wild, we may witness, explore, photograph, and write about the natural beauty of plants, their botanical diversity, visual complexity, fascinating life cycles, and valuable ecological roles—all within the thought-provoking and memorable settings of adventure and solitude. Encounters with nature and wilderness can reawaken our sense of awe and fascination. Such experiences help recalibrate our inflated estimates of 21st-century humans’ importance and degree of control over nature.

Many Americans, especially those who live in cities, manifest an unmet need to reconnect with nature in the wild, and so to regain an Earth-citizen’s perspective, rekindling – and validating—their passion to adopt a green lifestyle.

According to the Wilderness Act of 1964, wilderness is defined as an area of undeveloped federal land “that appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprints of man’s [sic] work substantially unnoticeable.” It is a place that “has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” [Section 2(c)]. It important to note that, for the purposes of this article, national parks, state parks, county and city parks, or even primitive private lands are not considered wilderness. Nor are they considered wilderness by the Act, although it recognizes them as “wild and valuable as compliments to lands contained within the National Wilderness Preservation System.”

So, where can you go in the U.S. to experience wilderness?

Today, slightly less than 5% of the entire United States—an area slightly larger than the state of California—is federally designated as wilderness. Over half of America’s wilderness lands are in Alaska, meaning that only about 2.7% of the contiguous United States, an area roughly the size of Minnesota, is protected as wilderness.

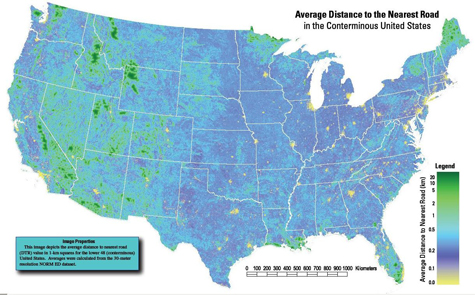

The Wildlife Conservation Society (2005) has created a human-footprint model to show the degree of a place’s “wildness” (lower numbers signifying greater wildness). Among the measures included in this model are human population density, amount of detectable human infrastructure for agriculture and habitation, the presence of industrial power (using the proxy of lights visible from space), and human access to land areas via roads.

For this latter measure, the Wildlife Conservation Society used the USGS Geographic Analysis and Monitoring (GAM) program’s high-resolution national dataset. Calculating the distance to the nearest road for all lands in the lower 48 states (c. 2005), it offers the first unified national view of roads, vehicle accessibility, and road-less spaces.

Pronghorn confront a highway in their annual migration through the Green River Basin of Northern Wyoming

Photo: Joe Riis

Usually, roads are detrimental to any land’s ecological integrity. It has been estimated that roads impact the ecology of at least 22% of the land area in the lower 48 states. Roads typically fragment habitat, eliminate forest canopy, elevate temperature, increase noise and pollution, alter natural drainage, introduce invasive and domestic species, kill road-crossing species, initiate anthropogenic fires and extinguish natural fires, and, of course, increase human presence in the landscape. All of these changes destroy the wilderness.

The road network of the United States consists of more than 4 million miles of mapped roads (this figure doesn’t include the hundreds of thousands of miles of private routes). When added together, U.S. roads and their rights-of-way occupy about 1% of the total land area of the United States. They constitute one of the largest human impacts on Planet Earth. To get an idea of the magnitude of this human construction project, imagine an area approximately the size of South Carolina completely paved over—dedicated entirely to roads. On average, in the lower 48 states of the U.S., you are never more than about 12 miles away from a road, anywhere.

USGS Map Depicting the Average Distance to Nearest Road (DTR)

Image: Get Outdoors

In examining that USGS DTR map, note that, east of the Mississippi River, just 4 states (Minnesota, Maine, Louisiana, and Florida) offer the deepest wilderness opportunities, while west of it, there are 10 states that do (Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, California, Arizona, and New Mexico). Only 6 states do not have federally designated wilderness areas: Connecticut, Delaware, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, and Rhode Island.

Some cautionary notes about the preservation and celebration of wilderness: Noted UW-Madison environmental historian and professor William Cronon thinks the passion to save wilderness “poses a serious threat to responsible environmentalism” because it allows people to “give ourselves permission to evade responsibility for the lives we actually lead….to the extent that we live in an urban-industrial civilization, but at the same time pretend to ourselves that our real home is in the wilderness.”

In addition, award-winning UC-Berkeley environmental journalism professor Michael Pollan also warns us that the wilderness ethic may lead people to dismiss areas whose wildness is less than absolute. In his 2003 book Second Nature: A Gardener’s Education, he writes that “once a landscape is no longer ‘virgin’ it is typically written off as fallen, lost to nature, irredeemable” (p. 188). Before undertaking any wilderness trip, one must consciously strive to avoid such flawed thinking. Ecological awareness and action can’t be limited to far-off, “special” places.

Haydn Washington, an ecologist and wilderness advocate, demonstrated that the term wilderness is beset by a tangle of meanings—philosophical, political, cultural, eco-judicial, and exploitive. In seeking common ground, he pointed out that one can view wilderness as one end of a spectrum of “naturalness” (2007, USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station). This seems logical to us, given that most scientists and conservationists today agree that no place on earth is completely untouched by human impacts—due either to past occupation by indigenous peoples or through global processes operating within the hydrosphere and atmosphere.

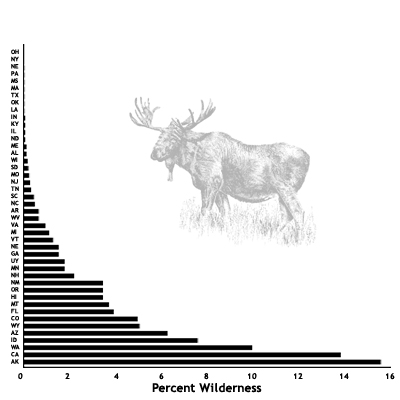

Finally, be aware that many people consider large mammals emblematic of wilderness areas. This chart produced by the National Atlas of the United States® reinforces that stereotype. Why a moose and not a poplar tree?

National Atlas Chart Showing Percent Wilderness by State

Image: National Atlas

Aristotle’s “scale of nature” concept has greatly influenced Western thought—even in the 21st century. He contended that there existed, in effect, a ladder of life in the natural world, the Earth’s organisms arranged on rungs from relatively simple to extremely complex. He held that life on Earth developed within a sequence of increasing complexity and interest from inanimate objects to plants and to animals to humans. So it is not surprising that we see a moose and not a plant dominating the image on this government chart. Alternatively, arguing from a visual cognition perspective instead of a historical perspective, we have claimed this bias to be attributable to plant blindness.

Now for some personal questions: How close are you to a wilderness area?

What kinds of native plants would you like to see in a wilderness area?

Have you experienced a wilderness lately?

If not, why not plan an immersive wilderness trip somewhere in the US to take advantage of the opportunities for personal growth and renewal. Learning about a site’s geological features, its characteristic plant life and history prior to visiting a wilderness area, you’ll anticipate each wilderness trip more eagerly and the trip itself will be uniquely interesting. In addition, you’ll find repeated visits to the same wilderness site can vary dramatically by season of the year.

Wildflower (eponymous?) in Maroon Bells Wilderness area of Colorado

Photo: Clare and Ben

Time spent away from everyday stressors, while surrounded by interesting plants could improve your quality of life. Fortunately, many people are just a day’s drive away from a designated wilderness area. Here’s a state-by-state list of National Wilderness Preservation System sites.

The lasting pleasures of contact with the natural world are not reserved for scientists, but are available to anyone who will place himself [sic] under the influence of earth, sea, and sky and their amazing life.—Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Comments

Inspiring post, Renee and James. Interestingly, NJ has two wilderness areas to NY State’s one. (There is a bit of a rivalry between the Garden State and the Big Apple state.)

I am in agreement with H. Washington’s “spectrum of “naturalness”.”

I just came back from Yellowstone 2 days ago. We saw lots of fireweed. Very beautiful, so was the paintbrush (very red in color). We saw many large wild animals and birds, the only animal we didn’t get to see was the pronghorn. Thanks for your post.