Human Flower Project

Twin Towers : Himalayan Mayapples

Plantsman Allen Bush was on a collecting trip in Sichuan, China, on 9/11. Ten years later, he remembers the helplessness of distance and the security gained from two tiny companions, their feet on the ground.

Alpine flowers on the way to Zhe Duo Pass, China

Photo: Pam Spaulding

By Allen Bush

I was with a group of plant explorers in Kanding, China on the evening of September 11, 2001. We’d just finished dinner. One of our Chinese drivers, known as the Wrench for his mechanical skills, knew I liked to check emails. He asked me and Pierre Bennerup if we wanted to go to an Internet café.

We’d been in China for over a week and were scheduled to travel throughout western Sichuan for another three weeks. Internet access was widely available across China, usually on very slow dial-up modems. Even in remote towns where farmers were herding yaks down a rutted muddy street and laundry was being done on a rock down by the river, you could find the Internet. Competition flourished with one café in the Sichuan mountain town of Moxi charging $2.00 an hour, another down the street charging a cutthroat $1.00. The smoky cafes were filled with teenagers playing shoot ‘em-up games.

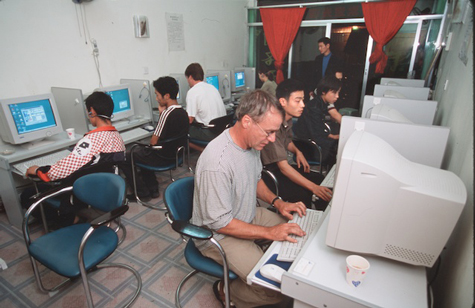

Allen Bush (foreground) at the Moxi, China, Internet Cafe

September 7, 2001

Photo: Pam Spaulding

The Kanding Internet café was down a long, darkened hallway on the second floor of a back street building. The Wrench behaved as if we were on a clandestine mission. His body language suggested the cafe was illegal. The small room, lighted by ten computer monitors and a matching number of flickering cigarettes, was packed.

The Wrench barked orders to no one in particular and three kids jumped-up, making room for us. I sat down at a computer to see what was going on. The keyboards were grimy which made it tedious to type a simple email when letters got stuckkkkkkkkk. The Yahoo home page had no news. The Wrench was occupied and I went back to the home page. I’d logged on just a few minutes before and now there was news that a plane had hit the World Trade Center. I presumed it was a small private plane. There were no pictures and no accompanying details. It didn’t seem especially troubling.

When I finished on the Internet, it was after 9:00 p.m., twelve hours ahead of Eastern Standard Time in the United States. Cigarette smoke clouded the room. I motioned to the Wrench. I was ready to head back to the hotel to clean seeds and so returned. He had other plans; the Wrench winked and wandered off into the dark.

Pierre, my roommate, and I poured a drink of whisky and laid out seeds to clean. We turned-on the television.

Drying corn and satellite dish, Sichuan, China

Photo: Pam Spaulding

The new Chinese affluence was marked, in the hinterlands, by a satellite dish on top of a block building. You could drive through small towns and tell who was rolling in dough. A single room, often lighted by a bare light bulb hanging from the ceiling, was the new community meeting hall. Villagers huddled around, mesmerized by news, sports or even a program devoted to obese Chinese trying to lose weight. (I didn’t see any obese Chinese during the month-long trip.) Television was my distraction while cleaning seeds in the late evenings.

Hans Hansen cleans seed in Sa De Guest House, China

Hans Hansen cleans seed in Sa De Guest House, China

Photo: Pam Spaulding

Pierre turned in. I stayed-up to update the log of the daily accessions I was collecting for Jelitto Perennial Seeds. And I needed to keep-up with seed cleaning. I went to work kneading the hard seed from the fleshy pulp off Chinese Jack-in-the pulpits. (The pulp on Jack-in-the pulpits can cause a toxic skin reaction. Latex gloves are an essential protection.)

That evening, around 11:00 the news came on, and there was an image of a jet slamming into a large building. I couldn’t understand the language, so there wasn’t anything decipherable about the unfolding tragedy. At breakfast the next morning the news turned frightening. Our Chinese guides had been playing cards late the night before and understood the news and the effect it would have on the Americans. Two planes had crashed into the World Trade Center towers that came crashing down a short time later.

The morning revelation was painful and the uncertainty hurt more. My daughter Molly was twenty years old and living in New York.

Our Chinese guides decided we should go to the Kanding post office and call home. From one of the two post office phones, I reached my wife Rose in Louisville a little after 10:00 p.m. EST on the evening of September 11th (It was then early morning, September 12th, in China). The connection was clear. We didn’t have much time to talk since others needed to make calls, too. Rose said Molly was fine. I can’t recall a time when I have felt such relief.

Rose told me that the president had spoken to the country a few minutes ago. She wasn’t sure what was in store (Was Louisville safe?) but did say that all flights into and out of the United States were suspended. Our group couldn’t go home. Rose said I might be better off in China.

Himalayan mayapple (Sinopodophyllum hexandrum) on a hillside near Kanding, 9/12/01

Himalayan mayapple (Sinopodophyllum hexandrum) on a hillside near Kanding, 9/12/01

Photo: Pam Spaulding

My plant explorer friends heard similar messages from home. We misunderstood this as, “Have yourselves a merry time wandering hillsides collecting plants and seeds, while we’re hunkered down at home with no idea when the next attack might come.” The comment hurt because, of course, there wasn’t anything we could do. We couldn’t go home. We were stuck. It took weeks before we realized that the comments weren’t petulant at all, but rather a warning that, indeed, we might be safer in China. No one in the United States knew on the evening of September 11th what was going to happen next.

As I left the post office, Paul Jones, Curator of The Culberson Asiatic Arboretum of The Sarah P. Duke Gardens, http://www.hr.duke.edu/dukegardens/ who’d organized the trip, called me over. I told him Molly was ok. Paul was standing with our resident botanist, Professor Zhao Zuocheng. Paul told me the professor’s daughter was living in New York, also. He couldn’t reach her. His English was halting and my Chinese limited to a few basics, but the look in his eyes communicated a common fear. I told him I’d email Molly and ask her to call or email his daughter. Molly found-out later that afternoon that the professor’s daughter was safe. He and I have, now for ten years, shared a bond of unspoken gratitude for daughters we love so much.

Along a village road north of Kanding

Photo: Pam Spaulding

So, there we were, ten Americans standing outside the Kanding post office wondering what to do. Should we stay close to the Internet news to follow what progressed back home in the hours ahead? That seemed likely only to increase our anxiety. We decided that it would be a waste of time to contact the consulate.

We didn’t have sufficient time left to make a long drive that day, so we agreed to head-out for nearby hillsides and return to Kanding that night. We’d go looking for plants and seeds—business as usual. Kanding is at a crossroads – a co-mingling of ethnic Han Chinese and Tibetans. We would head over the over the Zhe Duo Pass (4,296 metres/ 14,094’) a few days later where the architecture and culture are predominantly Tibetan.

Ozzie Johnson crossing a stream north of Kanding, China, September 12, 2001

Photo: Pam Spaulding

It wasn’t a long drive that afternoon. The pavement soon came to an end and we were slipping along a muddy road, past a small village where pigs roamed freely. We thought we’d gone as far as we could, but the drivers got us through the slop and beyond the village. We drove another few minutes and stopped.

It was a comfort to be back on a new hillside even though this clearly wasn’t uncharted territory. Commercial collectors had dug peony roots for medicinal use and left empty holes a short time before. On any other day we would set a time to be back at the cars and then would wander off on our own (time alone is a vital resuscitation when traveling in close quarters). But I didn’t want to be alone that day. Pierre and I kept close. If we were ever out of sight of one another, we’d call ahead to see where the other was. Our colleagues kept close, too.

Two boys from the country show up to lend their eyes, hands and spirit to the plant collectors north of Kanding.

Two boys from the country show up to lend their eyes, hands and spirit to the plant collectors north of Kanding.

Photo: Allen Bush

I never imagined this day would have any other value besides what plant and seed goodies we might find, but it turned-out to be a day I will never forget. Two little boys, showed-up out of nowhere, roaming a hillside overgrazed by yaks. We looked at one another, not with suspicion, but with great curiosity. The boys must have wondered how we’d come into their world. Perhaps they had never seen westerners before. Maybe they had never been to Kanding, a bustling market town, less than an hour away.

These Tibetan boys will never know what a comforting presence they were. Their angelic round faces and huge, beaming brown eyes were a quieting, peaceful alternative to the sorrow a half a world away. There were no Internet cafes, no satellite dishes – not in this remote hill country of western Sichuan. The world I knew, or thought I knew, seemed no longer a safe haven. I desperately wanted to be at home – in my crazy world – but couldn’t go back. My blessing was the reassuring company of two young boys. This world – their hillside—was a safe place.

The boys had sharp eyes. They helped us find plenty of bright red seedpods on Himalayan mayapples that looked like bright red banana peppers. They enjoyed the hunt, and Pierre, Pam Spaulding and I enjoyed the hunt with them on September 12, 2001. Twenty minutes or so—then these heaven-sent angels disappeared onto the hillside.

Pam Spaulding is a photojournalist who traveled with the plant explorers in 2001. The author and HFP thank her for kind permission to post these photographs.