Human Flower Project

Down on the Digital-Dirt Divide

For plantsman Allen Bush, it all began by getting shooed out of the house. After digging holes to an imaginary China, he’s actually gone there, collecting rare species and befriending rarer horticulturalists from across the world.

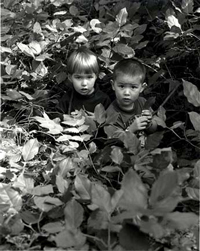

A youth spent in the woods leads to self-esteem, and in some cases, to a career and schanpps, also

A youth spent in the woods leads to self-esteem, and in some cases, to a career and schanpps, also

Photo: Jonathan Prescott

By Allen Bush

I wish children could experience the same simple pleasures I enjoyed over fifty years ago. They should try to dig a hole to China. My big adventure was slowed by summer heat and hard clay, but I finally busted through, on a plant hunting trip in 2001. Memories of abandoned, shallow craters from childhood expeditions in Louisville are nearly as good as Sichuan itself turned out to be.

Back in those early years, I imagined I could poke through by noon and be home by dark. But the only way kids are going to dig to China now is if they hack into Chinese cyberspace. American youngsters can’t be bothered with a spade. And they’re certainly not spending much time outside, unless you count a precious few minutes misspent with older brothers and sisters who stand shivering at the back door catching a smoke.

The digital-dirt divide worries me. Edward O. Wilson understands outdoor lessons: “The Secret Places of childhood, whether a product of instinct or not, at the very least predispose us to acquire certain preferences and undertake practices of later value in survival. The hideaways bond us with place and they nourish our individuality and self-esteem,” Wilson writes in The Future of Life. ”If played out in the natural environment, they also bring us close to the earth and nature in ways than can engender a lifelong love of both.”

Generation Z may learn again how to dirty their mitts and swing on a wild grape vine across a skinny creek, but it doesn’t look promising.

Among American children, ages eight to eighteen, more than seven and half hours are spent each day wired to smartphones, music/video devices, computers and televisions – sometimes multitasking several digital gizmos at once—according to a study conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation. And there’s no “Thank God It’s Friday” for this demographic. Bleary eyes are focused 24/7 all week long—which amounts to a whopping fifty-three hours —barely seeing the light of day. Stop and smell the roses? Doubtful.

Aster novae-angliae has been renamed Symphyotrichum novae-angliae

Aster novae-angliae has been renamed Symphyotrichum novae-angliae

Photo: MOBOT

I’ve just returned from the Third International Perennial Plant Conference in Grünberg, Germany, where I spoke on The Wildflowers of the Blue Ridge. The whole week was an adventure. In anticipation of the second colossal February east coast snowstorm, I flew to Baltimore two days ahead of my scheduled departure and was picked-up by my friend, Ed Snodgrass, who drove me to the farm he shares with his wife, Lucie, near Belair, Maryland. I worried that predicted snow in Louisville and in Philadelphia, a few days later, might delay my connecting flight to Germany. Ed, an author, nurseryman, and leading green-roof consultant, was planning to travel with me and to speak on Plants for Green Roofs. Our flight from Philadelphia to Frankfurt, scheduled for Wednesday evening, got cancelled with white-out blizzard conditions that brought 50 mph winds and an additional 20″on top of the 24” that had fallen the prior weekend. So we waited-out the storm. I shoveled snow and hauled in a few loads of firewood. But Ed did the heavy lifting: snow plowing and worrying about the extra weight of snow drifts on the farm office’s flat green roof. Lucie, an author in her own right and also Maryland State Director for U.S. Senator Barbara Mikulski, worked from home. I felt awkward about taking-up space, but Lucie and Ed were gracious hosts, as always. Ed enjoyed some company for 2 nights of televised college basketball games, but he wisely abandoned his travel plans. He had a farm to dig out.

Instead, Ben Crocker, one of Ed’s young mainstays, came in his place. Ben and I got out on Thursday afternoon and caught the Philly flight to Frankfurt. A bright, talented twenty-one year old, Ben got a big, big dose of plants before traveling onto England for another week.

Some of the participants in the Third International Perennial Plant Conference, Feb. 2010, in Grünberg, Germany: (l-r) Jan Spruyt, Peter Gaunitz, Hans Kramer, Marco Hoffmann, Allen Bush, Christian Kress, Coen Jansen, Pavel Křivka, Gerben Tjeerdsma and Georg Uebelhart (kneeling)

Photo: Courtesy International Hardy Plant Union

Over eighty gardeners, teachers, nursery folks and designers—who’ve spent a lot of time outdoors—arrived from patches of North America, and Europe, unimpeded by blizzards, to listen to talks sponsored by the International Hardy Plant Union. Topics ranged from Plant Exploring in Argentina to The Caucasus and its Flowers and Endemic Plants of the European Mountains. I was in high cotton for two and a-half days with tales from faraway places and revelations of “self-seeding vagabonds” from a talk on Perennial Prairie Plantings in Belgium. (I wanted to start singing Roger Miller’s “…a man of no means, King of the Road.” Maybe it was jet lag?).

Two talks, Searching and Crossing New Varieties and Protected Names May Sell a Plant but They Don’t Guarantee a Good One, urged breeders to spend a few more years, with their newly patented and trademarked plants, growing them in a variety of gardens and climates, before they unleash the marketers on a gullible public. Eager gardeners may be growing skeptical with claims of can’t go wrong. A presentation on Modern Landscape Design in Sweden was particularly inspired, and Nomenclature of Perennials—A Never Ending Story was just that—a never ending story.

You could bet on a lively conversation in Grünberg, on recent botanic name changes. Gardeners become accustomed and even fond of some plant names, and they hate to give them up. In 1737, Carolus Linnaeus, who tamed the nomenclature of the plant and animal kingdoms with his binomial naming system, once said: “Good heavens! When I consider the fate of botanists then I truly doubt whether their obsession with plants is normal or insane.”

Linnaeus couldn’t have foreseen the development of DNA identification. Sorting-out Who’s Your Daddy in the Plant Kingdom previously required only a hand lens and the close scrutiny of flower parts. Proof positive now resembles the work of a police lab. After years of argument, the outcome—with irrefutable evidence presented here: The Snakeroot genus Cimicifuga becomes lumped with Actaea. Cimicifuga, a Latin name so lovely to pronounce (sim-ih-sih-FEW-ga) gets tossed on the compost heap. There’s plenty more name changing to come. The New England Aster, formerly Aster novae-angliae becomes Symphyotrichum novae-angliae. For the middle-aged and older in the crowd, who love the simplicity of a name like aster, and who already have trouble keeping track of the car keys, it’s not good news.

I owe the invitation to speak at the Grünberg conference to my mother. She kicked me out of the house, after breakfast each morning in the summer of my sixth year. An accommodation was allowed at noon, back at the house, for a grilled cheese sandwich on white bread and a bowl of cherry flavored Jell-O, before I was sent packing again until dinner. (There were dinner bells, back then, that summoned home some of the kids for another wholesome meal of processed foods.) Mom didn’t like her backyard despoiled by my Chinese point of departure, but there were other options. The scruffy little woodlot at the end of my suburban road, generously named Country Lane, would be my happy hunting ground. It was at the other end of a world that stretched nearly one-half mile in any direction.

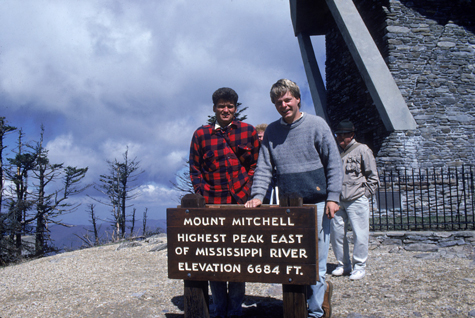

Author Allen Bush with Ratzeputz, the potion that drew him into a brotherhood of horticulturists from around the world.

Author Allen Bush with Ratzeputz, the potion that drew him into a brotherhood of horticulturists from around the world.

Photo: Courtesy Allen Bush

It took another thirty years for my life in plants to come into full bloom. There was an epiphany that year—neither the first nor the last – but life took a huge turn: I had my first shot of Ratzeputz – German-styled ginger flavored schnapps.

By this time, I’d been in the nursery business in the mountains of North Carolina, growing rare and unusual perennials for seven years. I was invited to travel to visit German gardens and perennial plant nurseries in the summer of 1987 by Maryland nurseryman Kurt Bluemel. Klaus Jelitto, founder of Jelitto Perennial Seeds, organized the tour. Eight of us piled into a slow-moving Volkswagen van that got passed on the autobahn for ten days by speeding cars that filled-up the rear view mirror faster than you could say “Lamborghini Diablo.” I didn’t know anything about German gardens. Great Britain, with over one thousand years of garden history, had long been my envy and focus. That was about to change.

The Bundesgartenschau, the remarkable German biennial garden exhibition, was held in Düsseldorf that year.

Children set off the fountain at Düsseldorf’s Bundesgartenschau, 1987

Photo: Allen Bush

There were plenty of towering Delphiniums, and newly bred Sedums and ornamental grasses. But I especially remember the children. Instead of being dragged around – so often the case—by weary parents, they were entertaining themselves. As families strolled through the gardens, they eventually came along a traditional evergreen allee—the sort that you might see around Europe. But carved into the Arborvitae hedge were spaces for dozens of rabbit hutches. Odd, I thought. The children stopped and stared at the bunnies nose-to-nose, amused, swept away in a moment of wonder, engaged in the outdoors. Not so odd at all! And they loved another feature where they splashed and laughed. Big, over-sized spoons scooped-up water, and when tilted like a seesaw, water came pouring-out the other end. Boys and girls nearby would jump up and down on cylinders, and the hydraulic pressure would squirt fountains of water everywhere. It was an idea as simple as putting wheels on a suitcase. Somebody had to think of it. And somebody in Düsseldorf did think of it. A stroke of genius brought joyful kids into the garden.

One evening during the 1987 tour, the group settled in after dinner at the rathskeller bar of the Heide-Kröpke hotel near Celle. Someone offered-up a round of Ratzeputz. Toasts were made. Down the hatch went the wickedly, ill-tasting drink. My first taste of Ratzeputz was a gateway sip to new friends, gardens, plants and ideas.

Plantsmen Georg Uebelhart and Cassian Schmidt visited Western North Carolina, Allen Bush’s old stomping and sprouting grounds, in 1988

Photo: Courtesy Kurt Bluemel

We’ve traveled again and again, every few years, under the banner of the Ratzeputz Gang, obsessed as we are, looking for new plants. I soon met Georg Uebelhart. He came from the Arnold Vogt Nursery in Zurich, Switzerland, and apprenticed with Kurt Bluemel in 1987 – 1988. Cassian Schmidt was apprenticing the same year. Bluemel brought them to the North Carolina mountains in April 1988 and we stood amazed, looking at woodland hillsides covered with white flowering Trillium grandiflorum. We spotted an occasional Yellow Trout Lily, Erythronium americanum, and tasted the flavorful lance-shaped leaves of Ramps, Allium tricoccum, a native wild onion. Uebelhart and Schmidt worked with Ed Snodgrass who, then, was Bluemel’s farm manager. Klaus Jelitto hired me in 1995 where I still hang my hat as Director of Special Projects. Uebelhart is now Jelitto’s co-owner and General Manager, and Schmidt is Director of Sichtungsgarten Hermannshof.

Ratzeputz is an acquired taste that I’ve not yet acquired. Nobody who visits me in Louisville comes begging for a drink, but I keep a bottle around to remind me of how lucky I am to have good friends, a garden and the outdoors.

My love of plants was definitely fostered by lots of outdoor play – in our backyard, in neighbors’ yards, in fields…!