Human Flower Project

The Arts & Crafts Garden: It Did Fly

From the Edwardian garden, down a slippery slope to many purposes. Or was it up?

Essay and photos by John Levett

In her chapter on “The Arts and Crafts Garden” in her [still] wonderful book The English Garden in the 20th Century, Jane Brown refers, in turn, to Gertrude Jekyll’s Gardens for Small Country Houses. I had a copy of it many decades ago but gave it to a friend when a new move couldn’t house all my collection.

The ‘small country house’ designation is relative. What we think of as a small house in the country these days might easily have referred to the gamekeeper’s cottage in the long-weekend of Edwardian England. Nevertheless, Jekyll’s recommendations are still adapted and muddled through albeit with less of the hard graft that it took then. If I were to redesign my garden now, I’m sure I’d find a copy and hatch a scheme accordingly.

That thought came to me a week ago before the snow arrived. I’d just finished the tidying up of the climbers and ramblers, finished pruning the deadwood and started tying in. Standing back and taking note of what else I could be doing before February is out, it came to me that a redesign over the next couple of years might be prudent. I’ve taken a few falls off the ladder in the past couple of years and the tall growths are getting to be ‘Small Country House’ size. Making changes would be a wrench. There are moments in late May when I sit there and want to be nowhere else. There are a ridiculous number of roses for this patch but I know why I built it this way and the reasons haven’t changed.

I think that maybe the turn-and-turn-around of garden life may push me into change. I think that three or four of the species roses (the earlies) have taken a dive. There’s usually a bud or two showing by now and, with the mild winter we’ve had, I should be seeing some growth; but not so.

Reading Jane Brown again I came across a small entry that hadn’t registered the first time around. She notes that Jekyll had listed a number of architects “… all given the accolade of good design, of approved Englishness.” One of the approved, alongside the blessed Unsworth, Voysey and Lutyens, was the young M.H. Baillie-Scott. He had published, in 1906, Houses and Gardens and incorporated his philosophy of planning and planting. (Note to self: dwell briefly on ‘philosophy in garden’—get some.) Jane Brown notes that Baillie-Scott started us on the slope that led inexorably to the multi-functional modern garden. Brown writes: “Edwardian gardens were for pleasure and to provide a decorative background for beautiful people. Baillie-Scott slated ‘this modern conception of beauty, allied solely to uselessness.’” After slating the extended functions that crept into the Arts and Crafts garden, she continues: “He has started us on the slippery road that crams ever more different uses — swimming pools, children’s playgrounds — into an ever small space. The quality of repose in the Edwardian English garden is in danger of being lost forever.”

One of Baillie’s creations was 48 Storey’s Way in Cambridge and I often pass it on long walks beyond the city. I met it first when walking towards Madingley Road to photograph Churchill College. (There was a long debate when the college was first mooted as the original designs omitted a chapel, thought to be an essential component of any university foundation.)

48 Storey’s Way

Storey’s Way is one of those buildings at which I always stop—The Arts and Crafts Example. Arts and Crafts stuff has a strong pull on the English imagination. I think I should capitalise that fully to The English Imagination. Of what that Imagination is constituted is worth a lifetime’s study— ‘Romantic Moderns’ by Alexandra Harris is a fine starting point. But, however radical I think I am, I recently bought the collection of Adrian Boult’s 1950s recordings of Vaughan Williams symphonies, started searching for the remaining four LPs to complete my 1960s Boult and Previn recordings of them and have begun collecting Roger Quilter, Ivor Gurney and Peter Warlock songs.

Arts and Crafts enthusiasm in this country must derive, in part, from the influence of William Morris and the radical-revolutionary undercurrents of the late nineteenth century and the Edwardian years. Inside many members of a workers’ party there is a love that daren’t speak its name—its name is Utopianism. Morris, Marx (Eleanor), Carpenter, Stopes, Salt, Schreiner, Fawcett—bung them all in the mix and some elevation of the soul is bound to occur. (I leave out Shaw and the Webbs where elevation of the ‘sole’ would be appropriate; putting them in the wagon with Randall Flagg.) Whatever its source, it has always drawn me in and for the Utopian come-on as well.

Cambridge has always had that A&C USP. When I first started day-tripping here it was for the books. Michael Holroyd’s biography of Lytton Strachey started me off; Russell and Wittgenstein; the Darwins followed. Cambridge has never been as radical as it would like to think but it has a slowness, space to ramble and enough green space every yard to support a thought of not-quite being in the age of capitalist hegemony with the last of the social fabric being ripped up and the nation sagging to Lear-like rot.

Kettle’s Yard

I walked into Kettle’s Yard yesterday to visit the house again. There are many in Cambridge who visit the house just for a brief sit. It has a quality to it that changes one’s sensibility. My mother died in 1979 and I spent a few years living with the remains of decoration-as -was. Then in the early 1970s I travelled to Cambridge for an exhibition at Kettle’s Yard: it was the house that took me.

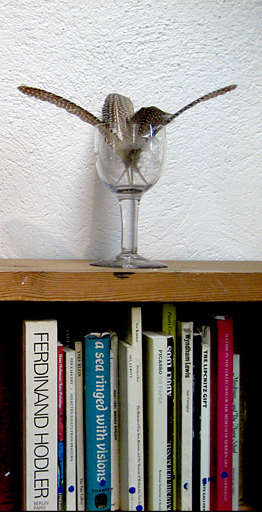

I was about to write that I was taken by its unclutteredness but it’s full of clutter that Jim Ede (the former owner) took a shine to and thought should have a home: pieces of wood, rock, shore-line scavengings, shapes that fit, shapes that echo, feathers in glasses, parts of a tool, shards—something in the catch of an eye, an urgent need to reclaim for memory’s sake what we carry with us far beyond the childhood aggregation of discards.

After that visit I came home and sketched, planned, designed; removed, covered; painted, plastered, sewed; sawed, nailed, attached. I framed, embroidered, patchworked, sculpted, lit. I transformed a small semi-detached in Hitchin into a collector’s item. The garden grew in tandem—each spring the collection added to from the most obscure specialist nurseries I could find. A few years back I intended to make the old trips again but so many had passed away (“Round up the usual suspects”).

After that visit I came home and sketched, planned, designed; removed, covered; painted, plastered, sewed; sawed, nailed, attached. I framed, embroidered, patchworked, sculpted, lit. I transformed a small semi-detached in Hitchin into a collector’s item. The garden grew in tandem—each spring the collection added to from the most obscure specialist nurseries I could find. A few years back I intended to make the old trips again but so many had passed away (“Round up the usual suspects”).

Every trip to Kettle’s Yard I’m caught by the same impulse. Looking around my own room now I note the purposefully-placed items; there for the purpose of reminding, reconstructing—the catalogue of the exhibition, the programme of the performance, the postcard of the room, the sketch of the idea, the saucer, the cup (1989, Coin Street market with …)

I think there’s also the trope of the home-made, the artisan, the craftsperson. I’m thinking of the ‘heroic’ here, the long march towards the sunny uplands; not the short trip round the corner to the boutique craft shop for beads & glitter spray. The carving, the moulding, the casting, the hewing; generation past generation building Rheims cathedral—that sort of heroic.

Ede was a collector of the paintings of Alfred Wallis. Wallis used whatever materials he could lay his hands on; it never mattered what, just so long as he could keep on painting. I thought of Wallis a few months ago when I was trudging through John Holloway’s ‘Change the World Without Taking Power’ and ‘Crack Capitalism.’ I took some of the ideas from those and modes of Cultural Exchange began to form; ‘gifting’ along the lines of Lewis Hyde’s exposition on gift economies. A couple of us in one of the groups I convene have started making works for each other from found materials. It’s an attempt, a ‘crack,’ at working ‘outside’ capitalist social relations. One can never do that entirely as Morris found out; Fry too, after a fashion, with his Omega Workshops. But there’s always a promise that an idea will take off and, even if it only flies a few feet and crashes, it did fly and the idea’s not dead.

When I was out starting off in the garden before the snow fell, I had pretty much the same sort of feeling—everything in process. Whatever happens in this garden, it’s still going to be a garden, and if a plant only takes for a season then it was still worth the candle, and labour’s never wasted because each act teaches, and connections are never only made with the materials but with others who labour too. Gardening is voluntary labour; most labour isn’t. John Holloway makes a distinction between the ‘doing’ and the ‘done’; that the ‘doer’ never retains the ‘done’ under capitalism; never ‘takes it to market.’ I keep the ‘done’ when I’m ‘doing’; it’s why I’m uplifted even if some of the plants are taking a dive. Ends are always beginnings.

I stated reading Jane Brown’s history to refresh myself about Jekyll and Lutyens and carried on to finish it. It’s good to connect with the history of this stuff and get a reminder that the idea of gardening ‘architecture’ is not a recent appropriation for the sake of making a fast buck.

I also jotted a list of garden visits I’ve never yet made. More follows.