Human Flower Project

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

Stormy Flowers

Many hurricanes and typhoons have been named, incongruously, for flowers. So why don’t earthquakes have names, even floral ones?

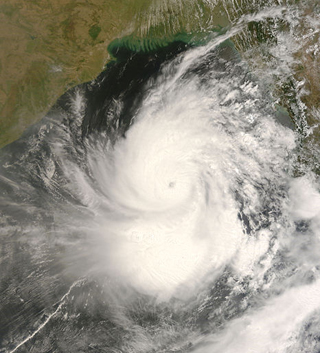

Nargis, 5/1/08, two days from landfall in Myanmar

Photo: NASA

Does this look like a narcissus flower to you?

It’s cyclone Nargis, nearing landfall on the Irrawaddy River delta in Myanmar (Burma). More than 62,000 are dead or still missing since the horrific storm hit on May 3. (The Red Cross now says as many as 128,000 people may have died.) Andrew Kirkwood, who directs Save the Children in Myanmar, told the International Herald Tribune that 3000 schools were destroyed.

So how strange that this cruel freak of nature bears the name of the daffodil flower. Nargis means “narcissus” in Urdu.

Nine days after the cyclone tore through Burma, a powerful earthquake shook central China, killing an estimated 10,000 people in the Sichuan province. Monday’s 7.9 magnitude temblor remained nameless.

Why would societies name some forms or natural disaster, not others? And why, in some instances, would they choose flower names for anything so immense and destructive?

Author Ivan Tannehill contends that the tradition of naming hurricanes began in the West Indies. There, storms were named after the Catholic saint on whose holy day they occurred—“for example, Hurricane Santa Ana which struck Puerto Rico with exceptional violence on July 26, 1825, and San Felipe (the first) and San Felipe (the second) which hit Puerto Rico on September 13 in both 1876 and 1928.”

Tannehill credits Australian meteorologist Clement Wragge with first naming storms for women in the 1800s. The custom seems to have spread among weather casters during World War II, and in 1953 the U.S. made the giving of women’s names to hurricanes official practice. (Men’s names were added in 1978).

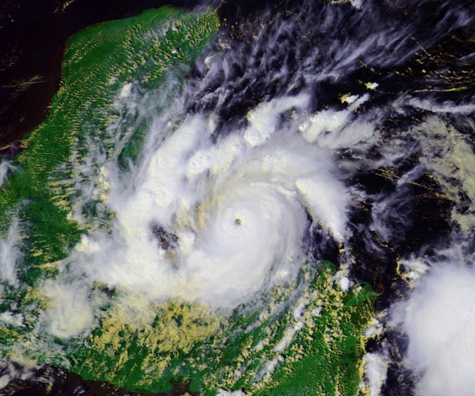

Hurricane Iris, spinning toward the coast of Belize, Oct. 8, 2001

Photo: NOAA

With so many women’s names being floral, there have been quite a number of “flowered” storms since 1953. Hurricane Iris, Category IV, tore across Belize and Guatemala, October 9, 2001. The storm killed at least 13 people, and left 10,000 more homeless.

In the U.S., anyone alive in 1969 will remember Hurricane Camille. Camille struck the Mississippi Gulf Coast August 17, 1969, creating the highest tidal surge ever on record in the U.S.

And one of the deadliest of all Atlantic hurricanes was Flora, in the fall of 1963. More than 7000 Caribbean island people lost their lives; 5000 people died in Haiti alone.

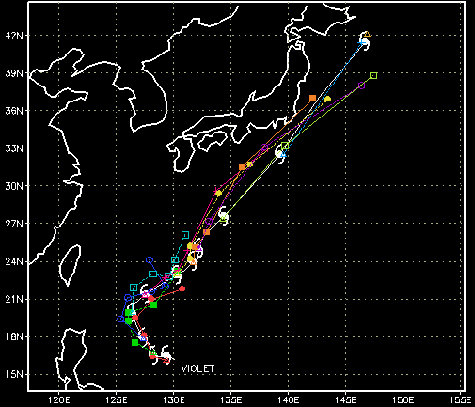

The path of Super-Typhoon Violet through the Northern Pacific

Image: UK Meteorological Office

In the Pacific, Typhoon Violet struck Japan September 22, 1996, a “record year for tropical cyclones.”

We have discovered that for Pacific and Indian Ocean storms, like Nargis (Narcissus), designations are far more complex than in the U.S., with our simple alphabetical list, alternating between men’s and women’s names. In 2000 the fourteen nations in the Pacific typhoon belt came up with their own system.

“The new names are Asian names and were contributed by all the nations and territories that are members of the WMO’s Typhoon Committee. These newly selected names have two major differences from the rest of the world’s tropical cyclone name rosters. One, the names by and large are not personal names. There are a few men’s and women’s names, but the majority are names of flowers, animals, birds, trees, or even foods, etc, while some are descriptive adjectives. Secondly, the names will not be allotted in alphabetical order, but are arranged by contributing nation with the countries being alphabetized.”

Looking at this Japanese site with all the fourteen nations’ current choices translated into English, we found lots of flower names, in addition to Nargis. Here are just a few stormy flowers waiting on the list: “Haitang” (flowering crabapples) a name from China; “Toraji”, meaning bell flower in Korean; and “Melor,” which is Malaysian for Jasmine.

“In the aftermath of a storm or hurricane,” writes V. R. Narayanaswami, “there can be a great deal of negotiation over insurance claims and legal issues related to the destruction to life and property. A name can more easily be handled than longitude and latitude as data or even direction and distance from a coastal town.” Makes sense. And perhaps the custom of switching from men’s and women’s names to trees and flowers spares people from future association with these tragic events.

But if so many nations have agreed that hurricanes and typhoons should have names, why not earthquakes too?

Here are two guesses (we welcome yours)—

*People sometimes can, and do, take measures to try to spare themselves from hurricanes’ destruction; having a storm name might help with evacuation and other emergency preparedness. But planning isn’t really possible with an earthquake. There’s little or no communication about the disaster BEFORE it occurs.

*Hurricanes and typhoons are water-borne and water-bearing disasters, churning in from the sea. And sailors have a thing for naming (just one example).