Human Flower Project

Friday, April 04, 2008

Pollution Snuffs Floral Scents

New environmental research shows how bad air is very bad news for bees, moths, and the flowering plants they visit.

After a long search for flower scent, this bee is fed up

—but still hungry

Image: Simpson Trivia

Does your life depend on perfume?

Ours does, and, conveniently, we can order another bottle of Mitsouko as needed. But many bees, moths, and other insects must rely on scented flowers—for food. The flowers they visit also depend on their own fragrances to reproduce, by drawing pollinators in.

A study by Quinn S. McFrederick, James C. Kathilankal, Jose D. Fuentes, published in Atmospheric Environment, shows that air pollution destroys the scent signals of flowers, an effect of bad air that makes pollinators less efficient and plant colonies less robust.

The scholars set up a model to trace how specific scent-producing hydrocarbons released from flowers react with major pollutants in the air: ozone, hydroxyl, and nitrate radicals. They looked at three particular hydrocarbons—linalool, b-myrcene, and b-ocimene—“known to be common scents released from flowers.” Introducing variables of wind and temperature, they examined how these “perfumes” would change as they encountered polluted air parcels. When the scent compounds react with the pollutants, they begin breaking down fast, becoming unrecognizable to pollinators (as when the ambergris disappeared from Dioressence).

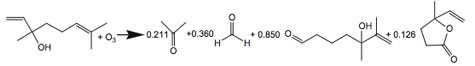

Linalool, a common floral scent compound, breaking down as it reacts with ozone

Image: Courtesy Jose D. Fuentes et. al

The scholars, from University of Virginia’s Department of Environmental Science, write that this feature of air pollution has not previously been studied, though they note that earlier research had found another threat to plants. Floral hydrocarbons (fragrances) also attract natural enemies of herbivores; as airborne pollutants like ozone react with floral scents, the “natural enemies” do battle elsewhere and the herbivores have, as it were, a field day.

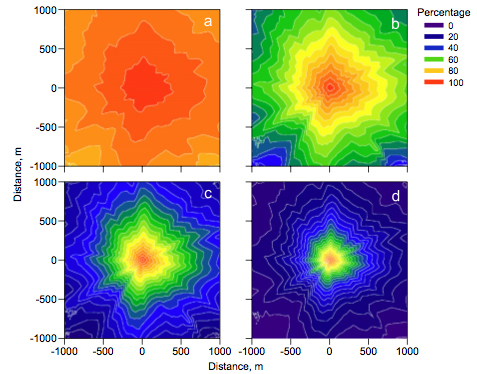

Charts showing how the range of floral fragrance compound linalool becomes smaller and smaller with increases in air pollution.

Image: Courtesy Jose D. Fuentes et. al

These charts, based on a Lagrangian model, show how dramatically interaction with air pollution limits the range of floral scents. The “scenario” at top left shows the dispersion of floral scent-compounds in a pre-industrial environment; the one at lower right shows what occurs in a highly polluted setting. The scientists write: “For highly reactive volatiles the maximum downwind distance from the source at which pollinators can detect the scents may have changed from kilometers during pre-industrial times to 200 meters during the more polluted conditions of present times.” Do you smell a problem?

Heads up, Judy Glattstein and other New Jerseyites! “These hydrocarbon–air pollution processes are likely operating in landscapes such as the eastern United States where summertime air pollution levels can become substantially higher than the ones observed in the rural atmosphere away from anthropogenic (a.k.a. human) influences.”

The scholars note that this impact of air pollution should be harshest on those plants that depend on “specialist pollinators,” since the chemical breakdown of floral hydrocarbons tends to blur fragrances, creating a generic “smell”: “what was a unique signal in the 1800s has become a general signal.” They also look ahead to research that might compare the olfactory receptors of insects in polluted and non-polluted environments—looking for signs of evolution. A thought: How about comparing the fragrances emitted by patches of city and country larkspur? Might flower scents be evolving too?

Many thanks to Dr. Jose D. Fuentes for sending us the paper.