Human Flower Project

Maps + OIL + Plants

Without detailed geological information about Block 252 in the Gulf and the chemistry of dispersants that have already been thrown into the water, how can we expect to clean up the coastal wetlands?

A dragonfly stuck with oil to marsh grass, Garden Island Bay, near Venice, Louisiana, May 18.

Photo: Associated Press

By James H. Wandersee and Renee M. Clary

EarthScholars™ Research Group

This past spring we had the chance to see the so-called Impossible Black Tulip of map collecting — the huge and detailed, 60-square-foot, 1602 Ricci Map of the World. It was on display at the Library of Congress before being moved to its new permanent home at the University of Minnesota. The James Ford Bell Trust bought the map for $1 million from Bernard J. Shapero, a noted dealer of rare books and maps in London, for the university’s James Ford Bell Library. The Ricci map had formerly been owned by a private Japanese collector.

Never before seen in the US, it is the first Chinese map to show the Americas, and was drawn and highly annotated by an Italian-born Jesuit priest named Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) when he was a missionary in China.

The Wanli Emperor had invited Ricci to become an advisor to the Imperial Court in 1601 because of his accurate scientific predictions of solar eclipses. Thus he was the first Westerner ever to be invited into China’s Forbidden City. Ricci placed China at the center of his map as a Jesuitical attempt to win converts to Roman Catholicism, while also exposing China to Europe and the Americas.

Father Ricci wrote, “This was the most useful work that could be done at that time to dispose China to give credence to the things of our holy Faith…. Their conception of the greatness of their country and of the insignificance of all other lands made them so proud that the whole world seemed to them savage and barbarous compared with themselves.”

Maps can indicate—and sometimes impose—great power. Today, we often assume that the maps we need are comprehensive, accessible to the public, objective, and unbiased. None of those assumptions is true. All maps actually distort reality in specific ways in order to depict some data better than others, according to their commissioned purposes.

Maps have also served as secret tools, intended to be used to gain a knowledge-advantage over one’s competitors. From ancient times onward, rulers have insisted that their countries be placed at a map’s center to convince others how important their kingdoms are. Only by being aware of the subjective omissions and distortions inherent in maps can we make sense of the information they contain.

Authors of Washington’s Blog wrote May 24, nearly a month ago: “We can’t understand the big picture behind the 2010 Gulf Oil Spill unless we know the underwater geology of the seabed and the underlying rocks…. We don’t know the geology under the [Gulf of Mexico Deepwater Horizon rig] spill site. BP has never publicly released its cross-sections of the seabed and underlying rock. BP’s Initial Exploration Plan refers to ‘structure contour maps’ and ‘geological cross sections,’ but all the detailed geological information, maps and drawings have been designated ‘proprietary information’ by BP, and have been kept under wraps.”

BP’s $560,000,000 Deepwater Horizon Oil Rig

Photo: BP

The BP oil spill is occurring in Block 252 of the “Macondo” Prospect in the Mississippi Canyon Area of the Gulf. Ordinary world citizens are blocked from fully understanding what is going on beneath this deep-water drilling site because they are denied access to the detailed geologic maps. Failing to release such information may also be preventing creative scientists world-wide from coming up with a workable solution.

The secrecy about Block 252 reminds us of the US Atomic Energy Commission’s “Area 51” in Nevada—the most famous secret military installation on the planet. For decades, the base remained hidden and unmapped, but in 1988 a Soviet satellite photographed the base and the resulting images somehow became public and provided a small glimpse.

While there may be good U.S. security reasons why Area 51 remains enigmatic and unmapped, we fail to see how U.S. taxpayers benefit from BP’s cloaked maps during the Gulf Oil Leak. BP does not own Block 252 or the vast Gulf of Mexico waters it is polluting. Shouldn’t national security take priority over profit-making secrecy? Is it wise to depend upon spiller-controlled problem-solving once BP triggered the largest marine ecological crisis in history along the U.S. Gulf Coast?

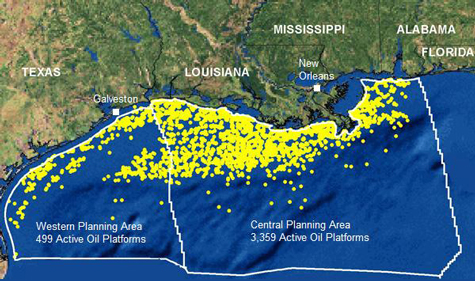

There are, at present, thousands of oil platforms located offshore along the US Gulf Coast. Each is first used in offshore drilling, housing as many as 130 workers plus the machinery needed to drill wells in the sea bed. These same platforms are then used to extract the oil and/or natural gas beneath them (or from nearby sub-sea wells); and finally, they process these extracted energy fluids, shipping or piping them to shore.

2008-2009 Map of Oil Installations along the US Gulf Coast

Map: The Gas Game

Oil platforms may be anchored to the sea floor or designed to float in place (the latter type can be moved to a new site by the oil company). There were about 30,000 offshore workers in the Gulf in 2010; the average age of rig workers is 27. They earn between $50K to $220K per year, but the work is not easy or without risk. A rig can bore miles deep into Earth’s crust to tap what can turn out to be a poisonous, corrosive, high-pressure pocket of petroleum. In fact, since the mid-1990s, oil and gas workers in the Gulf of Mexico have been dying in accidents at the rate of one every 45 days.

Why are all these oil rigs found in Gulf waters? The U.S. uses 22,000,000 barrels of oil per day (42 gallons = 1 barrel) and we cannot produce enough within the US to satisfy our nation‚s demand. Plus, the U.S. military uses 340,000 barrels of oil a day, making our American armed forces the single-largest purchaser and consumer of oil in the world (NPR, 2007). “BP…is one of the largest suppliers of fuel to the wartime U.S. military” (Bob Herbert, June 12, 2010, The New York Times).

While the U.S. must import about two-thirds of its oil at present, it seeks to reduce our dependence on foreign sources and so keep more of the billions of dollars that we spend on oil circulating within in our own economy. Yet global oil supplies, too, are finite and shrinking, even as our own demand and the world’s demand continue to rise. The estimated 50-million-barrel Gulf oil reserve that the Deepwater Horizon rig’s gusher is wastefully depleting would have satisfied the country’s current demands for less than 3 days.

“Petroleum, or oil, formed from the [buried] remains of plants and animals that lived in the ocean between 10 to 160 million years ago, ” explains University of California at San Diego’s Earthguide. “The lack of oxygen in the sedimentary layers caused organisms to slowly decay into carbon-rich compounds.”

The American Petroleum Institute (API) says that an average barrel (42 gallons) of crude oil, once refined, will produce 46% gasoline, 22% diesel fuel, 10% jet fuel, and 5.5% heavy fuel oil. The remaining 16.5% can be used to produce other petrochemical products: lubricants, asphalt, petrochemical feedstocks, synthetic rubber, and a variety of plastics. Thus, each barrel of crude oil yields less than 20 gallons of gasoline and less than 10 gallons of diesel fuel at the pump.

When crude oil is spilled by the oil industry, as in the Gulf, it exposes living organisms—plants included—to a potentially harmful “chemical stew” containing well over 1,500 different chemicals. Both the water and the air that plants need for everything they do, from food-making to nutrient absorption to gas exchange to metabolic processes to thermoregulation, are affected by an oil spill.

Saltwater marshes, such as those along the perimeter of the Gulf of Mexico, serve as protective nurseries for plants, shrimp, fish, birds, and other wildlife. And it is the plants the both undergird and sustain the base of these fragile ecosystems. They are ranked as one of the most environmentally sensitive ecosystems to remediate after an oil spill. It is even harder to clean an oil-polluted marsh than it is a beach. “You can’t pressure-wash a marsh,” said Dr. Denise Reed, a respected environmental scientist in Louisiana.

Worker power-wash a shoreline after an oil spill

Photo: Dr. Kent Simmons

Louisiana’s saltwater marshes wind through 7,700 miles of bays, reefs, passes, and estuaries and comprise 41% of the nation’s coastal wetlands. Such wetlands are an essential link in 75% of the fish and shellfish commercially harvested in the US. Louisiana’s fishing industry, the source of one-third of all domestic seafood consumed in the U.S. (1 billion pounds), is expected to lose as much as $2.5 billion due to the BP Oil Spill Disaster, and Louisiana’s Gulf-related tourism, $3 billion. Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, and Texas also face such Gulf-dependent eco-economic scenarios.

Aquatic plants can survive if they are not completely oil-coated. The most common wetland plants, common reed and smooth cord grass, both grow more than a yard tall, so they should partially stand above the encroaching oil slick. But it’s not just marsh plant leaves that scientists are worried about. Oil chemicals, both in water and in air, can interfere with many normal life processes in plants. For example, root systems are as important as leaves to sustaining plant vitality.

Once the oil enters and penetrates the coastal marshes, biological solutions for major ecosystem remediation all have downsides. Burning oil-coated plants releases noxious gases and can harm plant roots if water levels are inadequate, leading to soil erosion. Low-pressure flushing via water diversion only works when crude oil is floating on the water’s surface, and it can also erode fragile marsh soils. Sometimes the least-damaging solution is to allow natural bioremediation to occur. Most ecologists estimate that it will take years for ecosystems to recover from this oil spill.

A potential plant-impacting “wild card” in the 2010 Gulf Oil Disaster is the presence of hundreds of thousands of gallons of chemical dispersants that have been pumped into the Gulf of Mexico waters by BP to try to stop the leaked oil from reaching the fragile coastal marshes of Louisiana.

Once again, corporate secrecy is a factor. “Corexit, the dispersant BP is currently using, contains six chemicals. The exact recipe is a secret, according to Corexit’s manufacturer, Nalco, but it contains a surfactant and a solvent. Surfactants are long molecules that are hydrophilic (water-seeking) on one end and oleophilic (oil-seeking) on the other….Dispersants have never been applied on this scale, leaving environmental scientists guessing about the [ecological] consequences” (http://www.popsci.com/science/article/2010-05/how-do-oil-dispersants-work). Many of the saltwater marsh micro-organisms that support plant health produce their own chemical dispersants. We don’t know how the synthetic chemical dispersants will interact with these natural ones.

Oil coats the base of marsh grasses at Queen Bess Island, near Grand Isle, Louisiana, June 10.

Photo: Reuters

Ecosystems are complex and not fully understood by scientists. The 2010 BP Gulf Oil Spill will no doubt increase environmental stress on the affected marsh plants or even kill them. Some important plant species will likely disappear. Nobody knows how much ecological damage this oil spill will do, or how long it will take to restore the Gulf’s large marine ecosystem and its peripheral coastal ecosystems. But we do know that all life on Earth ultimately depends on plants, Even the organisms that make-up crude oil were once plants or life forms that depended upon plants.

Understanding of maps + oil + plants can indeed help us address the current crisis. BP may be the proximal cause and convenient scapegoat, but let’s not forget that human societies’ global, ever-increasing, environmentally unsustainable thirst for oil-based products and oil-based energy is the ultimate cause of this disaster.

In 1968, ecologist Garrett Hardin published his famous essay on “The Tragedy of the Commons” in the academic journal Science. He warned that any “commons” or shared limited resource can be depleted by maximized self-interests of the users. The Gulf of Mexico is an interstate and international seawater “commons” of 600,000 square miles.

Elinor Ostrom, a U.S. political scientist, was awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics (shared with Oliver E. Williamson) for “her analysis of economic governance, especially ‘the commons.’” Ostrom’s research analyzes how humans interact with ecosystems to maintain long-term sustainable resource yields. She has identified eight design principles of effective and stable commons management that can be applied to help prevent Gulf resource disasters.

Even if oil-drenched birds are cleaned to live, will their plant-based habitats recover?

Photo: Michael Macor

According to a May 2010 Associated Press Poll, “the country is split about evenly over which priority is more important in considering drilling, with 49% choosing the need for the U.S. to provide its own energy and 47% picking protection of the environment.” The June, 2010 Global Warming Poll by Stanford University found that “huge majorities of Americans still believe the Earth has been gradually warming as the result of human activity and want the government to institute regulations to stop it.”

As long as we face the facts that oil is a finite and non-renewable resource and that our continued uses of it have increasingly negative short- and long-term ecological consequences, we can choose to transition expeditiously to clean and renewable energy—such as the kind that has long been powering the green plants in our biosphere.

Oil is a fossil fuel. It has been estimated that it took 98 tons of ancient plant matter to give us 1 gallon of gasoline today (J.S. Dukes, Climatic Change, 2003, 61(1-2), pp. 31-44). We can think of oil as stored solar energy, derived from ancient plants and the organisms that ate them. The entire biosphere is plant-based and solar-powered.

For some people, “only money talks.” So, in recent years, the value of the bio-geo services we receive from the Earth has been calculated in monetary terms for that “money-listening” audience. Humans benefit from a multitude of resources and processes that are supplied by natural ecosystems. These ecosystem services include clean water, water power, clean air, fertile soils, decomposition and detoxification of wastes, crop pollination, seed dispersal, biomass fuel energy, pest control, disease control, and the like. Research shows that resource preservation offers greater long-term economic gain than does resource-extraction-to-depletion.

The 2010 BP Gulf Oil Spill should serve as our alarm and transformation. We think it’s time for each of us to take action to help prevent more “tragedies of the commons” by refusing to “map” our way into short-sighted self-interests, and to champion sustainable use of our natural resources and One Planet Thinking instead. For starters, we need a bigger, better map!

Comments

Thanks for this great article with so many facts. It seems to me that the international community will have to intervene in this matter—it’s simply too big for the self-interested corporations who focus on profits and save money by taking shortcuts on safety and proper engineering. This underwater oil gusher will take out the economy of a large swath of the gulf states and poison the gulf itself for decades to come. But it can’t be allowed to poison the waters of the Atlantic. This is so maddening. I am going to contact my local power company and see if they would accept a proposal to provide incentives to help my city and its citizens convert to electric cars. We have to end our dependence on oil.

Pleased to see the reference to Elinor Ostrom’s work.