Human Flower Project

Listening to Chinaberries

Once prized for its wood, shade, vigor and medicinal properties, this immigrant to the Southern U.S. is now nationally maligned.

Flowers of the chinaberry tree (Melia azedarach)

March 2011

Photo: Human Flower Project

How did a tree that once inspired gratitude in the U.S. become a pariah? All of us who treasure (or covet) good repute want to know.

In the case of the chinaberry (Melia azedarach) it has something to do with 21st century nativist snobbery – the chinaberry being an 18th century “immigrant” from Asia. Also, since chinaberries reseed easily and grow up fast, they possess that happy heedlessness that sends much of the gardening and landscape crowd into a fit of irrelevance.

The chinaberry is an insult to American vanity, to be sure. But in our opinion it was American technology that really turned popular sentiment against these trees.

After their introduction in Charleston, South Carolina, chinaberries seem to have spread rapidly across the South. In the many decades before air-conditioning (which became commonplace only in about 1950), they were valued as fast-growing shade plants. In some places, including parts of Texas, they’re even called “umbrella trees.”

An anonymous writer for Wood Magazine wrote this lively encomium:

“Introduced to the sundrenched American Southwest and Mexico centuries ago for shade, the chinaberry embraced its arid new home and flourished. This cousin of mahogany from China relished the hot, dry climate and responded to it with rapid growth in even the worst of soil.

“Native Americans, Mexicans, and new settlers in the barren land welcomed the new tree. Indeed, people cooled off beneath its branches, but didn’t hesitate to fell it for wood they worked into rustic furniture and tool handles, and burned for fuel.”

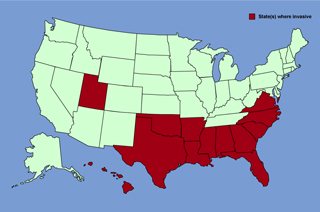

States where the chinaberry is considered invasive:

States where the chinaberry is considered invasive:

What’s going on in Utah?

In Southern reality the tree became ubiquitous; in Southern literature, the chinaberry became a kind of idyll, usually associated with plain or poor folks.

“From Mrs Littlejohn’s kitchen the smell of frying ham came. A noisy cloud of sparrows swept across the lot and into a chinaberry tree beside the house, and in the high soft vague blue swallows stooped and swirled in erratic indecision, their cries like strings plucked at random”: William Faulkner, The Hamlet.

Nowdays beside houses, shops and even air-conditioned barns there’s no need for chinaberry trees arching overhead. Nor are so many people willing to rely on its somewhat baffling “medicinal qualities.” For every one source that refers to its potency against “intestinal worms,” four more call it “poison” (to people as well as to worms). A book on the folk remedies of African-American slaves recounts, “People who ingest chinaberry may experience vomiting, irregular respiration, weakness, and increased salivation.” Sounds about as safe and effective as those pills advertized on prime time television, though we wouldn’t recommend it. Any of it!

A lot more reliably healthy than eating chinaberry seeds was using them as rosary beads. Again from Wood Magazine: “With frequent use, the seeds took on a lustrous polish, as if responding to the spiritual purpose.”

Brooks Kasson’s chinaberry tree, minus flip-flops

Brooks Kasson’s chinaberry tree, minus flip-flops

March 2011

Photo: Human Flower Project

Ever responding to spiritual purpose, our neighbor Brooks Kasson, who has a fine chinaberry in her side yard, nailed old flip flops in footsteps – green, white, yellow—along the tree trunk and lower limbs about a year ago. Ritual? Joke? Or statement of protest—Take that, Invasive Plant Police!!? Knowing Brooks, our guess is all of the above and more.

To be honest, we too have tended to dismiss the chinaberry as a “trash tree.” For ten years, they’ve kept sprouting in the no man’s-land behind the garage, and we’ve kept hacking them down. After all, we have air-conditioning. At the moment, we’re not troubled with intestinal worms, and we don’t (yet) pray the rosary. Nor do we possess Brooks’s imagination.

So what’s left?

Earlier this week, on a habitual mile-long loop through the neighborhood, we walked into a scent-island near the intersection of Park Lane and Newning, some sweet and powdery fragrance. It was floating from an old chinaberry tree on the corner. We’d never noticed the chinaberries in bloom before. Small purple starlets with maroon tubular centers, the little flowers hung in open clusters suspended on bright green stems: lilac-colored hairnets. They were delicate and completely stunning, and straining upward to sniff them, we began slipping hilariously on the fallen berries that had covered the sidewalk like marbles.

Chinaberries and flowers in Austin, Texas, March 27, 2011

Photo: Human Flower Project

We plucked off a low-hanging cluster and brought it home, adding it to a bouquet of bluebonnets and Archduke Charles roses. Five days later, the chinaberry’s powdery scent and tiny blooms are feebler but holding up pretty well. How many Southern flower lovers since 1780 have brought these blossoms inside with a shudder and respect, anticipating five months of summer and the chinaberry’s precious shade?

“Listening” is how the Japanese refer to the act of sensing fragrance – a good description of what happened that day at the corner of Park and Newning. Now that we have listened, it seems seems foolish and “deaf” that such a vibrant, beneficial and sweet floral tree could have become an object of scorn.

Chinaberry flowers, with bluebonnets and Archduke Charles roses, March 2011

Photo: Human Flower Project

For more, because there’s always more, please read O. Victor Miller’s highly strange account of the chinaberry in his own Georgia childhood. (Spoiler alert: a class clown pokes chinaberries waaay up his nose.) Miller concludes:

“Maybe Chinaberries are poisonous. Maybe they have a lingering and accumulative toxicity that has killed off all the people who used to live in tenant houses with Chinaberry trees in well swept hard dirt yards. Maybe the Chinaberry tree is an unrecognized historical cause of the downfall of the antebellum South.”

Might Melia azedarach do the same for Utah?

Comments

plant medicine works this way. if a plant makes you sick in a certain way. . when well, while if you feel the same kind of sick . . it becomes our medicinal fix. just breathing the air, of any plant, is the essence of nature’s finest and gentlest working medicines

(via Allen Bush….)

I love Chinaberry, Allen.

In the article, it alludes to the “Texas umbrella tree,” but this should be from the true-from-seed cultivar ‘Umbraculiformis’

Todd Lasseigne .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Paul J. Ciener Botanical Garden

Kernersville, NC

(Thank you, Allen….and Todd. JA)