Human Flower Project

Hand-in-Hand with a Passing

Not far from Legoland, a memorial to progressive engagement at Runnymeade, the riverside of liberty.

Princess Anne national savings stamp, March 1960

Image: Stampboards

By John Levett

In 1956 the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Harold Macmillan, introduced Premium Bonds, a variety of the savings scheme beloved of governments of the time—savings being seen as ‘a good thing,’ very worthy, a benefit to the nation and, given rising incomes and prosperity until the ends of time, possible in some way for most families. We even had savings schemes in primary school: bringing along our sixpences and shillings and our savings books. A working-class sixpence bought you a stamp with a Princess Anne on it and a princely sum of one shilling got you Prince Charles. These were stuck in a book and taken straight home to your parents lest you got the idea that you could trip straight down to the post office, take out your six-hours-old savings and blow the lot on ‘things that do you no good.’ Such a fact also led to a seriously-enduring dislike for the kids on the stamps.

The non-interest-paying Premium Bond (minimum deposit £1) had the come-on of the possibility of earning a monthly prize courtesy of the Electronic Random Number Indicator Equipment or ERNIE as it came to be known—in short, Britain’s first lottery; top prize £1000. The Gospel lobby was still strong in the Conservative Party of those days so according to debates all manner of societal breakdown was in store— a ‘cold, solitary, mechanical, uncompanionable, inhuman activity’ as the Archbishop of Canterbury had it. Mum bought some over the years but between 1958 and the year she died in 1979 only topped out at one £25 prize.

I’ve never been one for voluntary saving but when I retired from teaching I put a few grand into Premium Bonds (top prize these days, one million) and awaited the surprise. I never expected anything to happen; I looked upon it as a way of putting some money aside which would go to various charities in my will alongside the promise of random treats along the way. The surprise is that I keep winning. These are not amounts that’ll land me decreeing stately pleasure domes, rather a couple of CDs and a new shirt but they keep dropping through the letter box.

Edwin Landseer Lutyen’s kiosk, a memorial to Urban H. Broughton at Runnymeade

Photo: John Levett

This, of course, is fatal to the imaginative punter because if you’ve won fifty quid then there’s no saying that it won’t be a few grand next time and then Whooppee thereafter. I admit to wandering along the road of ‘Where would I live if I won the a couple of hundred grand?’ The curious thing is that I can never think of a decent reason for moving out of Cambridge and can think of two places only that I’ve ever dossed down in that have, from the first step off the train, felt like arriving home—Liverpool 1970 and Berlin 1993—the only places that I could (and did) say: “I could live here.”

Why I didn’t would take too long, but I got last week to thinking of where I’d never end up. Surrey topped the bill. E.M. Forster lived there in Abinger Hammer—the laureate of Surrey. Not the place to give rise to a Steinbeck, Akhmatova, Zola, Tolstoy, Dawish, Márquez, Herta Müller. I have no authority for writing any of this; I have only my imagination which tells me that Surrey’s stuffed full of footballers and their wives, stockbrokers and bankers, Tory-voting estate agents, building developers, imperialists, coup-plotting ex-army fascists, no-talent X-Factor judges.

So where is this leading? Last Friday I took myself off to Runnymede (Waterloo to Egham thence walk). Stepping off the train I didn’t find myself amongst my people. “Excuse me please. Could you point me in the direction of Runnymede?” “You mean the Runnymede Hotel?” “No. I mean that stretch of English soil close by the Thames which represents itself as the place from whence, it is alleged, emerged our current understanding of the Rule of Law and the foundation of various formations of the democratic idea. That Runnymede.” “Sorry. There’s a police station down there. They’ll know.”

Clearly, a fault line somewhere between my history learning and the contemporary market-driven Surrey-friendly version. If I’d asked for Legoland I’d have had no problem.

Why go there? This sort of place I should have been brought to by my mother. She was hot on history and no part of English soil went untrodden in search of some foundation stone, artefact, ruin, remnant of struggle that represented my heritage, birthright, culture, custom, roots. Runnymede got left off the agenda. Maybe she couldn’t stand Surrey either.

The reason for the trip was the Kennedy Memorial. It was designed by Geoffrey Jellicoe who lived for almost the whole of the last century and is unarguably one of the finest landscape architects of any age. Shute House in Wiltshire, Horsted Place in Sussex, Sutton Place in Surrey, Barbara Hepworth’s sculpture garden, the Hemel Hempstead New Town Plan and the water gardens there, Harvey’s roof garden in Guildford, the re-design of Fitzroy Square—in all of these there is a sensibility for human scale and humanity, for the non-material needs of the soul, for the space to pause, stop, wait and move that speaks of a moment when all was possible and all was within reach of us all in a shared communality of progressive democratic engagement.

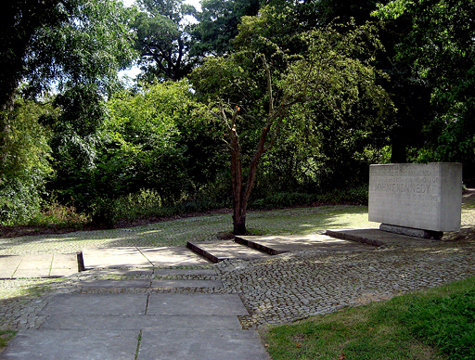

The Kennedy Memorial at Runnymeade

by landscape architect Geoffrey Jellicoe

All Photos: John Levett

”

I think the Kennedy Memorial at Runnymede speaks to that belief. The creation of each element of this remembrance is symbolic; from the bequest to the American people of the acre of English land upon which the memorial is built, along the steps of granite setts, through the unkempt woods, beside the scarlet American oak, the steps falling away to slightly-distant separated seats placed above the sloping meadow to the Thames—all represent an idea, a shared idea of how things might be.

Here’s the inscription familiar to a generation: “Let every nation know whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend or oppose any foe in order to ensure the survival and success of liberty.”

It’s easy to mock that and cast stones at its orator but maybe less easy to acknowledge how we were then. It’s equally easy to kid ourselves that we were born right-on, right-thinking, freedom riders who couldn’t be kidded on anything. I wonder if the kidding continues. Sitting for a long time within that space of the memorial it’s not difficult to remember the possibilities of that moment even if you were living above a street-end grocer’s shop in south London.

It’s easy to mock that and cast stones at its orator but maybe less easy to acknowledge how we were then. It’s equally easy to kid ourselves that we were born right-on, right-thinking, freedom riders who couldn’t be kidded on anything. I wonder if the kidding continues. Sitting for a long time within that space of the memorial it’s not difficult to remember the possibilities of that moment even if you were living above a street-end grocer’s shop in south London.

Jane Brown writes of Jellicoe’s creation: “The concept of a memorial, particularly this memorial, lends itself to the emphasis on the spiritual values of a place. In a garden that element of spirituality can be lightened to fantasy, and it is the element of fantasy, another country for the mind to explore, that Jellicoe believes the 20th century mind most longs for.”

The struggle for honesty, which every political struggle is, is not a fantasy. When the people gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial the night before Obama’s inauguration they sang for honesty. Nobody there in person or spirit could believe that the coin had flipped and come down ‘Goodness’ but when the words of Woody Guthrie piped up nobody there could have failed to detect within themselves a New Deal optimism.

Geoffrey Jellicoe’s architecture of the Kennedy memorial site is imbued with optimism and optimism is always hand-in-hand with a passing something. One moves through the wood towards a recognition and a recalling, passes through an acknowledgement and on to a possibility and an imagined elsewhere. Kennedy had the quality of creating the ‘imagined elsewhere’ and it would be foolish to deny it in hindsight.

Along the Thames at Runnymeade

We can make of any memorial what we will. To remember a moment of time, list a loss, state a fact of a person, illustrate a role, demonstrate a hierarchy—these are the stuff of most memorials. To bring into being a space for questioning past, present and future and to allow an interval for imagined possibilities is rare in an architect and such was Jellicoe. To sit there thinking only “Won’t get fooled again” is not enough. Such thoughts belong to the personal, to the self, to the restrained and the restricted; Jellicoe speaks to something more encompassing, more universal, more generous than our own sensitivities. Steinbeck: “This is the beginning – from ‘I’ to ‘we.’

I did not know this memorial existed. It is gorgeously executed. Thank you for sharing your observations with us.