Human Flower Project

Elizabeth Lawrence’s Confidante

A new book collects the letters of a beloved Southern gardener and the fellow North Carolinian who gained her trust and friendship.

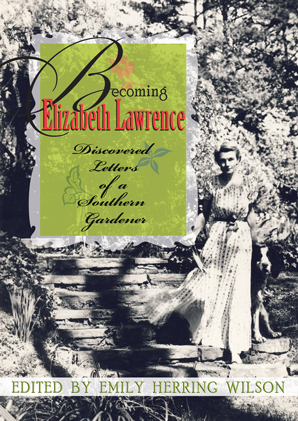

Friends and correspondents (l-r) Ann Preston Bridgers

and Elizabeth Lawrence

Photos: (Bridgers) The Little Theatre, (Lawrence) Warren Way and Elizabeth Way Rodgers

By Allen Bush

Becoming Elizabeth Lawrence: Discovered Letters of a Southern Gardener made me nostalgic for letters. I hadn’t even thought they might have gone away. But who writes letters anymore? Pen and paper seem as scarce as a porch swing.

Author Emily Herring Wilson discovered letters written – mostly typewritten—between Elizabeth Lawrence and Ann Preston Bridgers when she was doing research at Duke University on No One Gardens Alone, A Life of Elizabeth Lawrence (Beacon Press 2004). Wilson has gathered many of these friends’ letters, written between 1934 and 1966, a pre-Facebook and Twitter era. The collection is a revelation of life and culture you won’t find with the new social media. Elizabeth to Ann (1941): “Do my foolish letters bother you? I always have a feeling that you do not like me to write to you when you are working. But it is hard not to when I think about you so much, and like everything else, there are only two ways to write: a lot or not at all.”

Blizzards in Buffalo and tummy aches in Topeka are the stuff of Facebook. I dare you to find anything on Troilus and Cressida. Elizabeth to Ann (1934): “I read Troilus and Cressida because of ‘The Moon shines bright. —In such a night as this, where the sweet wind did gently kiss the trees, and they make no noise; in such a night, Troilus, methinks, mounted the Trojan walls, And sighed his soul toward the Grecian tents, Where Cressida lay that night.’ But I was cruelly deceived. I had no idea that Cressida would take a Trojan lover. Still I can’t think why you call it an unpleasant play. I thought it very funny, especially the part where Pander [Pandarus] praises Troilus to Cressida. I love the way the heroes of The Iliad are made over into English gentlemen. The battle scene reminded me of Journey’s End [1924 R.C. Sherriff play with all the characters determined to play cricket….]”

The Lawrence-Bridgers era was a slower time, when written communication was not restricted to one hundred and forty characters (Facebook is more generous with 420 characters) and opinions could be expressed without worry that the rest of the world needed to know. “I’m tired of writing to you. Come home. I want to talk. There are also things you can say but not write.”

Fans of Elizabeth Lawrence will be thrilled with this new book, and would agree with Wilson who calls Elizabeth “…one of America’s best known writers of classical garden literature.” Becoming Elizabeth Lawrence will only strengthen their depth of feeling. Wilson points out what’s in store: “Although readers may learn a great deal about gardening in Lawrence’s books, less is to be learned about her save that she was a knowledgeable, generous, and witty gardener. She did not reveal a lot about herself, though the letters were filled with people and places, family and friends, writers and gardeners, who mattered a great deal to her. Elizabeth is visible half in the sun and half in the shadow, as through the garden gate.”

Fans of Elizabeth Lawrence will be thrilled with this new book, and would agree with Wilson who calls Elizabeth “…one of America’s best known writers of classical garden literature.” Becoming Elizabeth Lawrence will only strengthen their depth of feeling. Wilson points out what’s in store: “Although readers may learn a great deal about gardening in Lawrence’s books, less is to be learned about her save that she was a knowledgeable, generous, and witty gardener. She did not reveal a lot about herself, though the letters were filled with people and places, family and friends, writers and gardeners, who mattered a great deal to her. Elizabeth is visible half in the sun and half in the shadow, as through the garden gate.”

For others, not so wound-up with gardens or rare Amaryllids, Becoming Elizabeth Lawrence is the history of two writers who achieve acclaim during a time when professional success for single females was as challenging as bringing the white spider lily Hymenocallis calathina into flower—with its “strange, disturbing scent….” Wilson writes in the introduction, “All her life, Ann [Bridgers] had laughed at the Southern code of false chivalry that made men powerful and wives and daughters helpless dependents.”

Lawrence endured four lonely years in New York (1922-1926) as an undergraduate at Barnard and enjoyed periodic travels, but she was never truly comfortable except at home: “It is so nice to be home,” she writes. “I do not ever want to go away again.” The Bridgers family lived across the street from the Lawrences’ Raleigh, North Carolina, home. Ann Preston Bridgers, thirteen years older than Lawrence, would become Elizabeth’s principal confidante. Elizabeth admired her success and trusted her criticism and advice. Bridgers was the successful co-author of the 1927 Broadway show Coquette, starring Helen Hayes. In 1929, Mary Pickford received an Academy Award as Best Actress for her first “talkie” role in Coquette, the film.

Through nearly three decades of letters, one senses Elizabeth (the name by which she is principally known among gardeners) gaining confidence year by year, in spite of nagging self-doubt and periodic indifference and rejection from editors. The book is also a fascinating socio-cultural picture of Piedmont North Carolina, especially during the World War II years. Elizabeth to Ann (1943): “We have a little Nazi [sympathizer?] spending the night with us tonight. A nice little boy, too, and such a miserable wretch that I am sure that you would not feel sorry for him. But he is crazy….”

Elizabeth Lawrence in her Raleigh, North Carolina, garden

Photo: Elizabeth Lawrence House and Garden

Elizabeth depended on her mother, Bessie, who tended house and paid the bills, leaving her daughter free to write, study, garden and work on landscape designs in Raleigh and later in Charlotte (they moved next door to Elizabeth’s sister’s family in 1949). Elizabeth was the first female graduate in Landscape Design at North Carolina State College, now North Carolina State University, in 1932.

Ann Bridgers, triumphant in New York, never achieves popular success again after Coquette. She tires of the big city hustle —and perhaps love lost—and comes home in 1933, revisiting New York periodically for weeks, sometime months, or escaping to a cabin in the North Carolina mountains to write. In 1936, Bridgers helped start Raleigh’s Little Theatre, which remains successful today. Eventually, she settles in Raleigh to care for her aging mother and sister Emily, whose polio has worsened (Elizabeth is very close to Emily, too, and welcomes her literary advice).

A lot of familiar names from Elizabeth’s books re-surface; most are included in a handy outline of the book’s Cast of Characters. Krippendorf, Busbee, Hunt, Tong, the Dormons, and Weltys, are all back!

Elizabeth Lawrence’s house, 348 Ridgewood Ave., Charlotte, North Carolina

Photo: Elizabeth Lawrence House and Garden

After fourteen years as the Charlotte Observer’s garden writer, Elizabeth Lawrence was fired in 1971. She had written 720 columns and published books considered the best of American garden writing: Southern Gardens, The Little Bulbs and Gardens in Winter. But nothing gave her more pleasure than having a weekly audience with the popular Sunday column. Elizabeth’s gracious authority must have lost sway with the newspaper higher-ups. The paper’s editors relinquished years of experience, offering simpleminded How-To advice in place of daily garden observance.

Around the same time, the Cooperative Extension Service conceived the Master Gardeners program. After only a few weeks of gardening-made-easy instruction, aspiring homebodies could be anointed “Master Gardeners.” In her first Charlotte Observer column, 1957, Elizabeth wrote, “Never let yourself be deceived about the work. There is no royal road to learning (as my grandmother used to say). And there is no royal road to gardening – although men seem to think there is.”

Elizabeth was a masterful gardener and writer (though she would have cringed at such a notion). In 2004, Horticulture magazine posthumously named her one of the 25 greatest gardeners in the world. Considered shy by some (not so by others), Elizabeth was continuously encouraged and consoled by her dear friend Ann. Wilson writes in the book’s epilogue, “Perhaps Elizabeth’s letters to Ann Bridgers, more than anything else she wrote, best tell her story and deepen the meaning of what she said to her family near the end of her life: ‘I want you to know how much I have loved life and how necessary it was just the way I played it.’“

Comments

Reading anything by or about Elizabeth Lawrence is always something to treasure. I was so glad to find this post. Thank you for the review. I can’t wait to read this book myself.

Delighted to find this site.

Right now the lesser celandine which carpets my small woodland is in full bloom. After I had visited Mr. Krippendorf’s southern Ohio garden, now a public nature preserve, I remarked on the celandine in a letter to Elizabeth, saying I really wanted to dig up a few roots. Her response arrived in a tiny cardboard box—a few roots which her note explained had originated in Mr. K’s garden. The golden carpet is a seasonal reminder of Elizabeth.

My brief correspondence with her began as I was writing an entry on her for American Women Writers. They were handwritten as she was no longer able to type. And they were letters, in every rich sense of the word. Those letters are now in her archives-LSU, is it? But I made copies which I think I will hunt up and re-read.

I’m also reading this new book and my thought is the same. I miss letters. I have some old family letters and they tell me more about my relatives than I could have possibly found out even by talking to them and asking questions.

I’m enjoying this book, learning more about one of my favorite garden writers. It’s fascinating to read!