Human Flower Project

Einstein’s Flowers

The magus of modern physics accepted a big academic promotion with a display of flowers. What did they say (or withhold) that made roses better than a letter or a handshake?

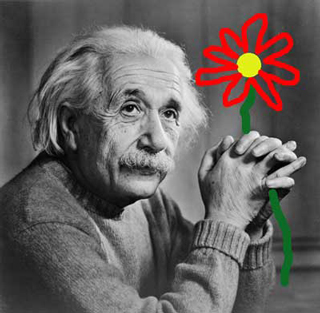

Albert Einstein, a poor gardener, used roses to accept

a job offer from Max Planck, 1915

Image: Meet the Germans

Are floral meanings relative?

Yes and no. We base that on our own reading and experience, and now on the pronouncement and the behavior of Albert Einstein, too.

His general theory of relativity is beyond the scope of the human flower project (or at least beyond our own analytic powers) but the chronicle, spare though it may be, of his personal floral interests and neglect certainly falls within our sphere.

In his early days as a scholar, Einstein worked as the equivalent of an adjunct professor in Bern and Zurich, Switzerland (one early physics paper concerned the capillary force of a straw). He landed a better appointment in Prague in 1911 as his ideas about the structure and behavior of subatomic particles, the effects of gravity on light, and other philoso-physical theories gained ground in the international community of science. The mighty theoretician seems to have enjoyed his teaching duties except insofar as they interfered with his own research.

Einstein and his second wife, Elsa, in Tel Aviv

Photo: Zionism and Israel

By 1915 he had returned to Zurich. There, “Einstein was approached by representatives of several foreign universities attempting to lure him away to their own institutions. One of these offers proved too good to resist: Max Planck, one of the most important developers of quantum theory, and Walther Nernst, a brilliant physical chemist, offered Einstein a professorship at the University of Berlin that allowed Einstein to teach only as much as he wanted.”

Planck threw in some other incentives – a top salary, membership in the elite Prussian Academy of Sciences, and leadership of a new research institute in physics. According to this biography site, “Einstein told Planck and Nernst that he would greet them the next day bearing red flowers if he chose to accept their offer, and white flowers if he declined. Unable to resist a position that would enable him to focus entirely on his relativity theory, Einstein arrived with red roses.”

Sadly, no one appears to have captured this human-flower incident on film.

Once moving to Berlin and settling in, Einstein did lease an allotment for gardening in Berlin-Spandau’s Kolonie Bocksfelde: “a handkerchief-size Schrebergarten.”

A Goethe blog deliciously recounts, “The great theoretical physicist called it his Spandau Castle and, according to contemporary reports, he was fully involved in the community, frequently calling on neighbours and visiting the colony’s restaurant. But his gardening skills were not as refined as his scientific gifts. In the end the allotment association grew disappointed by the standards of his weeding.

“‘Dear Herrn Professor Einstein,’ the local authority Bezirksamt Spandau wrote to him in 1922, the year he was awarded the Nobel Prize, ‘You presently lease Allotment No. 2 on the Burgunderweg in Bocksfelde. It has come to our attention that this allotment has been poorly managed for a considerable time. Weeds have spread over it and the fence is in a bad condition. These oversights leave an unaesthetic impression. If you do not put your allotment in order prior to the 25th of this month, we will assume that you are no longer interested in leasing it and will give it to someone else.’”

It’s tough to keep after the ragweeds and thistles when you’re cranking out history-makings statistics and off to meet to King of Sweden.

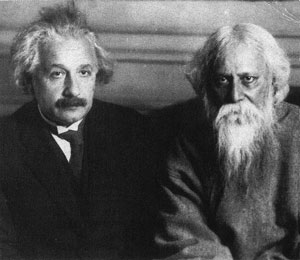

Einstein and Rabindrath Tagore

Einstein and Rabindrath Tagore

Photo: via Einstein and Tagore Plumb the Truth

A bit later on, in 1930, we catch up with Einstein and Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore. The two met at the scientist’s woodland retreat south of Berlin and discussed, among other things, consciousness, goodness, and music. Here’s an excerpt that intensely interested us.

“T: Once I asked an English musician to analyze for me some classical music, and explain to me what elements make for the beauty of the piece.

“E: The difficulty is that the really good music, whether of the East or of the West, cannot be analyzed.

“T: Yes, and what deeply affects the hearer is beyond himself.

“E: The same uncertainty will always be there about everything fundamental in our experience, in our reaction to art, whether in Europe or in Asia. Even the red flower I see before me on your table may not be the same to you and me.”

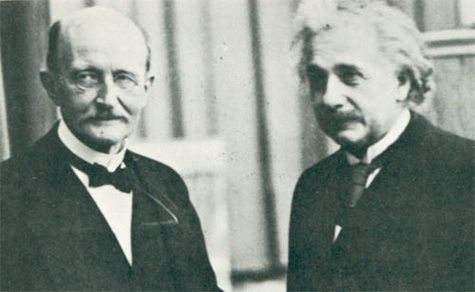

Max Planck and Albert Einstein

Photo: via Nova

May not be. Though, on the other hand, it may be entirely the same. The red flowers that Einstein brought to his second meeting with Planck and Nernst of course did mean – on the face of it— the same thing to all involved: “offer accepted.” Had it not been for the red roses’ capacity to communicate that message clearly, Einstein wouldn’t have suggested the symbolic gesture. But WHY he preferred using flowers to uttering or writing down his acceptance we’ll never know.

For the great scientist, maybe it was a matter of precision, as surely the ramifications of his move to Berlin would work out quite differently for all three men.

“Even the red flower I see before me on your table may not be the same to you and me.”

(Thanks to Bill Bishop for the Einstein-Planck anecdote, and for much else besides.)