Human Flower Project

Saturday, August 18, 2007

Clytie: Obsessive Heliotropic

Jealousy can turn your head around, and around. Just ask the mermaid.

La Metamorphose de Clytie (detail)

By Jean-Francois de Troy, Meaux, Musee Bossuet

Photo: Bill Bishop

For Roman poet Ovid, the natural world was the outcome of feeling. Plants, trees, rivers, and stars grew out of the old gods’ emotional entanglements. At death, a human hero beloved by some goddess, might be installed in the heavens: a new constellation. A virgin who fled one lusty deity could be transformed by another into a laurel tree just in time to preserve her honor.

The Metamorphoses, Ovid’s masterpiece, is really about how the inner life is inevitably exteriorized. Feelings bring change (often tragic) into the world. For the sea nymph Clytie the transforming emotion was obsessive love which, as it tends to, turned to jealousy. Clytie was fixated on Apollo (Helios) the god of the sun, following his every mile across the sky. When Apollo began a love affair with Leucothoe, Clytie went to the other girl’s father, a Babylonian king, and informed on them. In a rage, the old king killed his own daughter, burying her underground, out of Apollo’s sight.

Far from currying affection with the Sun God, Clytie of course had inspired his fury, and he refused ever to come near her again. But she maintained her fixation, tracing his ride across the sky each day.

La Metamorphose de Clytie

By Jean-Francois de Troy, Meaux, Musee Bossuet

Photo: Bill Bishop

The story appears in Book Four of the Metamorphoses. Here’s one translation of the finale:

“Shunning the Nymphae, beneath the open sky, on the bare ground bare-headed day and night, she sat dishevelled, and for nine long days, with never taste of food or drink, she fed her hunger on her tears and on the dew. There on the ground she stayed; she only gazed upon her god’s bright face as he rode by, and turned her head to watch him cross the sky. Her limbs, they say, stuck fast there in the soil; a greenish pallor spread, as part of her changed to a bloodless plant, another part was ruby red, and where her face had been a flower like a violet was seen. Though rooted fast, towards the sun she turns; her shape is changed, but still her passion burns.”

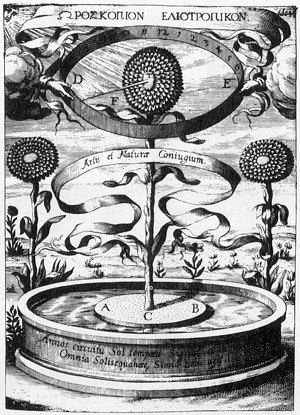

Kircher’s Sunflower Clock

Kircher’s Sunflower Clock

Via: Ursi’s Eso Gardens

The term heliotropic refers to plants that, like Clytie, rotate their floral “faces” in the direction of the light. Many commentators have concluded that the sea nymph turned into a sunflower (Helianthus). But we’re not so sure. Sunflowers are American plants, and not “like a violet.” Could Ovid have been referring to something more like heliotrope? It’s purple, and rotates with the movement of the sun, also. But it’s not native to the Mediterranean region either. Readers, can you provide more information or, at least, give us your thoughts on this human-flower mystery?

Certainly, many European artists have associated Clytie with the sunflower: George Frederick Watts (note the yellow blossoms in the background) and Jean Francois de Troy, whose Clytie wears her tournesol like a third eye.

After all this wringing emotion, let’s retreat to a bit of science—Kircher’s sunflower clock (discovered on the wonderful site Ursi’s Eso Garden). “To illustrate his belief in the magnetic relationship between the sun and the vegetable kingdom, Kircher designed this heliotropic sunflower clock by attaching a sunflower to a cork and floating it in a reservoir of water. As the blossom rotated to face the sun, a pointer through its center indicated the time on the inner side of a suspended ring.” Talk about obsessive!